The history of Kiyosato

“People who grow Kiyosato”

Yamanashi Prefecture Hokuto Takane-cho Kiyosato …. This land now visited by many tourists throughout the year, the Tokyo of water turtles, in the development of Ogouchi dam, was forcibly sent to Yatsugatake foothills Nenjoke original frontier people, overcame hardships beyond description , it was open land. Currently Kiyosato, summer seeking cool to plateau, winter and skiing, became a land where you can enjoy throughout the year. This is, people often do not take the other to the results that have been brought up this Kiyosato. To the people, even now, it is Natsukashimi endeared, will introduce the story of two great man of.

Paul Rusch

History of Dr. Paul Rush

- 1897 Born in Indiana, United States

- About 1900 Moves to Kentucky

- 1925 Comes to Japan for the first time to rebuild the Tokyo and Yokohama YMCAs

- 1926 Decides to remain in Japan as a professor at Rikkyo (St. Paul’s) University in Tokyo

- 1927 Re-establishes the Brotherhood of St. Andrew in Japan

- 1928 In response to Dr. Rudolf Teusler’s request, Rusch helps him to raise funds for the construction of St.Luke’s International Hospital in Tokyo (until 1931)

- 1934 Establishes the Tokyo Intercollege Football League

- 1938 Establishes Camp Seisen Ryo as a leadership training center for BSA

- 1942 Repatriated to the U.S. at the outbreak of war between Japan and the U.S.

- 1945 Returns to Japan as an officer for General MacArthur’s General Headquarters

- 1946 Begins planning the Kiyosato Rural Community Center (KEEP)

- 1948 St. Andrew’s Church is completed at KEEP

- 1949 Ohio Experimental Farm is established at KEEP

- 1950 St. Luke’s Clinic opens at KEEP

- 1957 Seisen Ryo reconstruction completed; St. John’s Nursery School opens at KEEP

- 1963 Kiyosato Farm School opens

- 1979 Died December 12th at St. Luke’s International Hospital in Tokyo

The Road to KEEP

Dr. Paul Rusch was born in Fairmont, Indiana and grew up in Kentucky. Rusch first came to Japan in 1925; arriving to work for the reconstruction of the Tokyo and Yokohama YMCA’s destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake. After completing his one year assignment for the YMCA he was ready to leave. It was the plea of Bishop McKim, then the Chairman of Trustees at Rikkyo Gakuin (an educational institution established by the American Episcopal Church), that persuaded the reluctant Rusch to “remain and teach at St. Paul’s University.” Despite Bishop McKim’s urging, Rusch did not change his mind about wanting to return home.

However, Bishop McKim continued pressing Rusch so enthusiastically that, at last, he succeeded in getting Rusch to reply, “All right, just one year.” This decision to become an educator significantly changed the rest of his life. During his days as a teacher, Rusch was profoundly touched by the enthusiasm of his students who trusted him. This made him start thinking seriously about devoting himself to supporting young people. Rusch, who wanted to give people hope through faith, dreamed of how to organize a group to support students. He encountered and was profoundly moved by the motto of “Prayer and Service” from the Brotherhood of St. Andrew in the United States. The motto inspired Rusch to establish a Japanese chapter of the BSA in the U.S. in 1927.

He was 30 years old at the time.

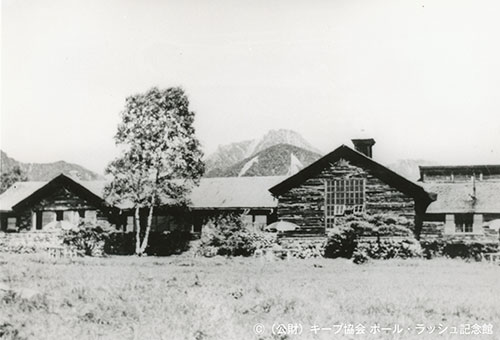

The next year Rusch was asked to work with Dr. Teusler on a fundraising campaign for the reconstruction of St. Luke’s International Hospital which was also destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake. In the process, Rusch mastered Dr. Teusler’s effective fundraising techniques and was introduced to the doctor’s vast network of personal connections. After the success of the fundraising campaign for the reconstruction, Rusch returned to Japan and started working on the new project for his own students. This project was the building of both a main office (St. Andrew House) and a leadership training camp for the BSA. In 1938, with support from many people, the long-awaited youth leader training camp was completed with a new name “Seisen Ryo.” The name takes one letter from each of the two villages where the camp was located; “Kiyosato” and “Oizumi”. It is said that Rusch loved the name “Seisen” which has another meaning of “Pure Spring.”

Around that time circumstances grew worse that led Japan and the U.S. into the Pacific War. Although Rusch resisted returning home even after he was the only missionary left in Japan he eventually had no choice. He was captured and detained in an internment camp on the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor and was repatriated to the U.S. in 1942. Upon his return to the U.S., he joined the U.S. Army and was assigned to the Military Intelligence Service Language School where he became a teacher and was assigned to assist Japanese-Americans working there.

In 1945, Rusch returned to a devastated Tokyo as a GHQ officer. Working to create a democratic nation newly committed to peace, he saw the urgency of rebuilding rural communities and cultivating mountainous regions.

Rusch retired from the GHQ and started to work on a new project at the foot of beautiful Mt. Yatsugatake; a site with a commanding view of Mt. Fuji. His model community, built around Seisen Ryo, became the core of recovery for villages and a model for rural development throughout post-war Japan.Rusch created a plan to produce food, to provide opportunities and facilities for receiving education and healthcare, to build a foundation for faith, and so on. In this way the Kiyosato Educational Experiment Project (KEEP) was born.

KEEP operations were not like an easy walk down a flat road. People had to cultivate the land where the soil were filled with many rocks and stones scattered during a prior eruption of Mt. Yatsugatake. There was no stable supply of water and people had to endure severely cold winters. People had to face realities which were not very easy to overcome. Rusch also had to face difficulties while he devoted himself to Kiyosato and what made him able to continue his work were both his own personal Christian faith and the people around him who understand and supported his project.

Referring to this difficult work Rusch used to say “I only taught how to do it, and it is the people of Japan and Kiyosato that actually have done it.” Rusch often traveled back to the U.S. on tours to visit many groups of supporters and fundraise for the Japanese people. One donor who listened to Rusch’s speech in the U.S. considered the importance of a tractor for cultivating the land and subsequently gifted a John Deere Tractor of Deere & Co. which had a high reputation for its horsepower. A John Deere Tractor Model B with a bright green colored body and yellow wheels was brought to KEEP in 1951. That donation created ties with the president of Deere & Co.at the time, Mr. and Mrs. Hewitt, who later personally brought gifts of tractors to KEEP. At the same time, a Jersey bull was donated to KEEP with the expectation it could survive the basic feed available and the severe cold in winter. The plan was if the bull survived the winter then a cow would be gifted the next year. The KEEP Farm was launched with the bull, seven cows, and a calf after the bull successfully survived until spring. This is the history and connection with John Deere tractors and Jersey cows that can be seen up until the present day at the KEEP Farm.

KEEP overcame countless difficulties as described in this history and became not only the key to the community development in Yatsugatake area but also became the rural community model for postwar reconstruction.

Do your best, yet there in first class

In 1955 the first Seisen Ryo building completely burned down right before KEEP was about to restart as an incorporated foundation. The people and children in the local community along with Rusch’s friends in the U.S. encouraged Rusch and saved him from bitter disappointment.

An enormous amount of funds were required to realize his plans that grew bigger and bigger, however many influential figures in various industries including Rockefeller and the American Committee for KEEP supported his project and provided funding for the venture. Not only that, KEEP received so many in-kind donations from anonymous people in the United States. It was Rusch’s extraordinary personality and enthusiasm that moved people.

People who knew Rusch well said he was a frank, friendly, and warm-hearted person with memorable smiles. He was short-tempered sometimes, occasionally lonely, and easily moved to tears. Rusch was indeed a great leader, but at the same time, he was just an ordinary person.

“Do your best, and it must be first class.” This is the directive given by Dr. Teusler, Rusch’s lifelong mentor and the founder of St. Luke’s International Hospital. Dr. Teusler taught Rusch, ”…if you do a job in the name of Christ, make it first class. … Nothing second class will do.” Rusch faithfully kept this philosophy for his entire life. Rusch devoted himself to the development of Kiyosato, continuingly giving hope for youth, and also committed himself to building friendship between Japan and United States.

In December 1979, Rusch passed away at the St. Luke’s International Hospital. He was 82 years old.

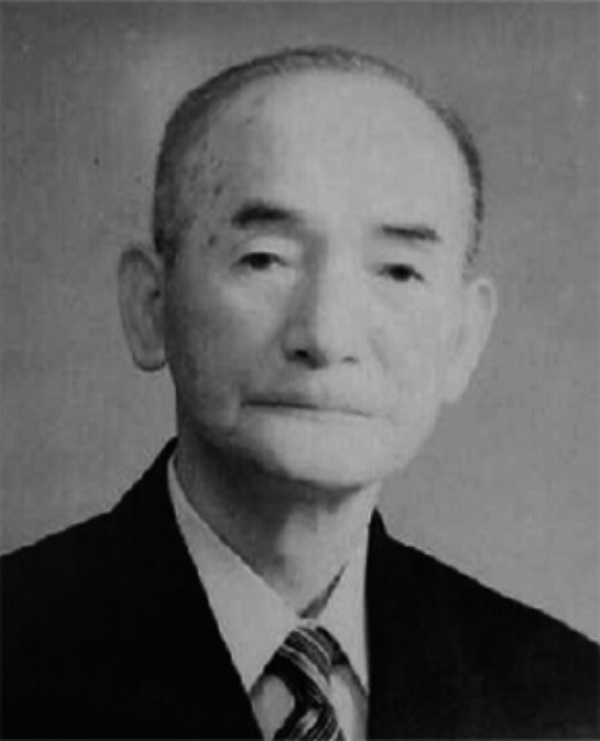

Okio Yasuike

In 1938, upon the construction of Lake Okutama, villagers from Tabayama and Kosuge who were about to lose their homes which were to be underneath the lake, moved to Kiyosato and started developing the area. Mr. Yasuike was a technical officer from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the time. He gave agricultural directions and lead the settlers.

It was such a hard work to grow crops in Kiyosato, where it is so cold that it is called “Hokkaido of Yamanashi.” Mr. Yasuike, however, regardless of his own life, continued to support the settlers by providing fertilizers and building a small branch school and so forth. These endeavors of Mr. Yasuike, with his bonds of friendship with the settlers, are still passed on down by word of mouth.

“Story of Kiyosato”

(Written by Yoko Kono. In Kiyosato, a picture book publication based on this writing is planned. It is aimed at handing down the story of hardship but full of trust and hope, to the locals and the visitors of Kiyosato.)

Kiyosato is a highland that has an elevation of 1,200 meters.

The water is cold, the sky vast, and Mt. Fuji seen afloat in a distance. Fall and winter are long with the minimum temperature going down to negative twenty degrees Celsius.

It may have been from 1898 when people started calling this highland in the foothills of Yatsugatake, Kiyosato. On February 15th of this year, former Asakawa and Kashiyama villages merged to become Kiyosato village. It was just a small village, nothing special.

In the summer, Kiyosato becomes a town of the young. The streets around the station, SEISEN-RYOU, Japanese accommodations, guest houses, coffee and souvenir shops all become packed with people, people, and people. A group of cyclists in red pants run through the meadows, and couples wait hand in hand for their turn to buy soft-serve ice cream.

Kiyosato has changed.

When we came to Kiyosato as settlers, it was a wilderness all around. Our home town is lying under the water of Ogochi dam system/ Lake Okutama which is called the water jug of Tokyo. To build the dam, as many as 945 households from three villages, Ogochi, Tabayama, and Kosuge, had to move to different places. We were making living by making charcoals and growing miscellaneous grains when swallowed by a monster called “The Grand Plan for the Future of Great Tokyo”. We could not speak out a word of opposition.

Furthermore, the city of Tokyo had changed its commitment again and again. Six years had passed when we finally left the village with compensation money. Villagers had lost their way of living and the fields and paddies went wild.

Only debts were piling up. We, the twenty-eight households from Tabayama village decided to move to the Nembagahara in the foothills of Yatsugatake to seek a new ground. Even though we knew that the settlemet is not yet ready for us to move in to, one member from each household gathered to form an advance party and started off from the village leaving his/her family behind.

April 17th, 1938.

On the way to Kiyosato at Kofu station, we were welcomed by a calm, fair-complexed young man. He was Mr. Okio Yasuike, the director of the office of Yatsugatake reclamation project of the agricultural land section of Yamanashi prefecture. When we arrived at Kiyosato station, the sky was marvelously clear. I, who was still young, exclaimed to myself “the dome of the blue sky is my home!”

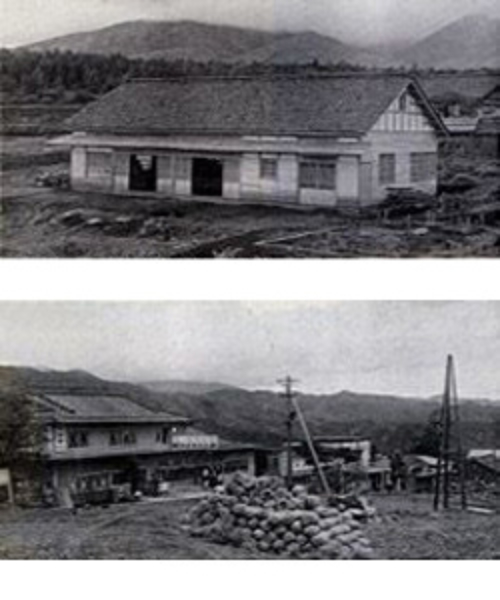

At first, a hoe was handed to each of us as a farming tool for the time being. From that day, life began, making the project office and the warehouse our temporal lodgings and sleeping on the wooden floor with our clothes on. The hardship was supposed to be for a brief period of time until we receive compensation from the nation and the prefecture to build our homes. But the compensation for transfer that we received was all gone when the piled-up debts were repaid. There was no other way of life but to stay here and survive.

How boundless Kiyosato is!

We, who were used to cultivate narrow strips of land on steep mountain slopes, were at a loss.

For the first week, Director Yasuike took us to Minamimakimura village in neighboring Nagano prefecture to study highland agriculture. Walking about and observing such people growing cabbages and Japanese cabbages in Nobeyama district and rice cultivation in Itabashi district where the elevations are higher than our Nembagahara’s encouraged us.

Director Yasuike made experimental fields with the three elements, nitrogen, phosphate and potassium for us for we lacked good knowledge of fertilizers. A piece of land of about half a hectare was allocated for each household. We used lottery to decide who gets which piece. Drawing was repeatedly done to be fair. To neutralize the acidic soil, lime was scattered, and seeds and seedlings of crops such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, soy beans, azuki beans, maize and field rice were distributed

We have to push ourselves hard and survive!

More than three months had passed. There was no sign of building of the housing we were promised to move in. Everyone was getting tired of living together. We made a proposal to Director Yasuike about building our own individual shacks.

Wisdom of building charcoal-making-cabin that we acquired in Tabayama was employed. Logs were assembled, barks were used to shell, and the entrance covered with a hanging straw mat. Even the largest one was merely about eight-tatami-mat large. Families were called in one after another. One family even brought their family tombstone on their backs along with their furniture. Children started going to Kiyosato elementary school, six kilometers away.

Our first harvest in the highland was daikon radishes. I cannot forget the joy of pulling each one out, holding its lush green leaves.

At Director Yasuike’s suggestion, farmers union was founded. The first shipment was two carloads of cabbages to a market in Osaka. Upon hearing their popularity, we took each other’s hands in joy.

To increase our cash income, we decided to hawk vegetables on Director Yasuike’s advice. We brought daikons and potatoes to Kofu on a freight car, stayed at Director’s official residence, and took turns to hawk in the city.

“Ma’am, we’re fine at the corner of the dirt floor, since we’re dirty”

“What are you talking about. Please come this way”

In our shacks, pine roots are constantly smoldering for light and heat. The smell of resin clung to our body and clothing and smelt strange. Regardless of that, director’s wife sincerely treated us as visitors. She even came with us to take orders for pickling daikons around the official residences.

At the beginning of November, it snowed on Akadake, the main peak of Yatsugatake. Step by step, it snows in places of lower elevations for the second and third time, and for the fourth time, it reaches the village. The long and harsh winter of Kiyosato begins.

Ultimately, we are to spend this winter in our shacks. Director Yasuike clearly seemed worried. He told us that on some nights, he stayed awake thinking about the coldness of the highland as he heard the crickets in space under the floor singing in chorus at his Kofu official residence. One more thing we were worried about was school attendance of children. On the six kilometer long way to school, there are hills and valleys. The path to Otaki is slippery and dangerous. How much snow fall can children stand to walk on? Adults have been worried and taking turns to accompany younger children to school. But there are too many things to do in the settlement. Time is precious for us. We, from the bottom of our hearts, hope to have a school near by. An eighty-year-old grandma had passed away. The trouble is that we have no place to bury her.

The village cemetery has become full, because quite a few people in the settlement has already died. Director is making a great effort to deal with the police.

Most of the dead so far have been old people and children. The environment is too awful. Even inside of the shacks goes to negative twelve, thirteen degrees Celsius in winter. Pickles in a bowl and leftover tea all get frozen solid.

“In any case, we have to build houses”

Director’s endeavors began.

Floor space 84.15 square meters, concrete foundation, a farm house with white plaster walls and a tiled roof. The breakdown of the 1,000 yen construction expense was 300 yen from the government subsidy, 100 yen from the prefecture, and 600 yen from the city of Tokyo.

The prices were rising because of the Sino-Japanese war and we were told that it was impossible with 1,000 yen. But when the housing was finally completed with our help for odd jobs, the settlement was in its second winter. It was in 1939.

Another headache also turned up. Children stopped going to school. With an elder child’s exclamation “Here we go!” as a sign, everyone threw his/her bag on the path in the mountain to play around all day and came back with an innocent look.

“Because everyone bully us by saying ‘immigrant children are coming’”

It was because of the smell of pine resin. However, no matter how much they were hated, if we stopped burning pine roots in the house, they will be shivering with cold in the dark. Parents started to want a school more strongly as they scolded their children. But to build a 330-square-meter-two-class-room branch school, it would cost as much as 12,000 yen. When Director Yasuike made efforts, with the cooperation of Ogochi dam construction office, city of Tokyo decided to provide 8,000 yen. However, the application of government subsidy, 3,000 yen, was simply turned down because “A branch school is a luxury for such a small developing land”

However, the company bit by bit asked for money needed for inflationary prices and when it exceeded the amount of contract, disappeared at once. The school house, which had just had its framework raised was standing in wind and rain.

Five households that were anxious and dissatisfied of the situation suggested that they would want to leave the cooperation. They wanted their houses and fields, but be free of their actions and leave the union, from then on. How selfish. “We do not want to go down together. We cannot follow you, anymore” As a parting shot, they said to Director Yasuike who was worried about them, and left us. Those were the ones with some left over compensation money.

Usually calm Director Yasuike gave a fiery speech. That extinguished our anxiety that we had had deep down in our hearts since we arrived here, of his going somewhere sometime, and helped us make up our mind to become able to take care of ourselves while this director is around.

“I decided to borrow money from my father in Shizuoka. With that, let’s complete the construction of school” Director left for Shizuoka accompanied by two delegates. Noting Director’s absence, the carpenter came with people from those five households to take building materials and tools from the site.

Informed of the emergency, we hurried to the site. At Kiyosato station, scene of carnage was almost created in the dusk. However we kept larger materials, they took every nail, wire and bolt wrapped in a blanket. During this military-charged period, it was difficult to obtain materials. “We need to notify Director Yasuike”

We could not wait for the first train the next morning. At ten in the evening, we, the young two, ran down the forty-kilometer mountain path with lanterns. We indeed were tired when we got to Nirasaki at dawn, dozed off for a while on the rock in front of the station, and arrived at the official residence in Kofu at eight in the morning. Uninformed Director and others were cheerfully having breakfast after having been successful to get the loan. Director seemed to understand something grave had happened as soon as he saw the two of us. “Why do you have to suffer so much. You were sacrificed for people of Tokyo…” Tears flowed down on Director’s cheeks as he held us, who were crying like babies, in our hands.

Hunchbacked elder ones are bringing tea.

Little ones are picking up small rocks to clear the way. People on and under the roof are signaling each other.

Director Yasuike is nailing boards in the corridor. We were lucky to have a young man with carpentry skills. As the saying “Work together around the clock”, we completed the construction that experts said would take six months, in as few as twenty days. All the people from twenty-three household burned and burned to complete the construction for twenty days. A small branch school was built in a windbreak forest in Kiyosato highland. With only two class rooms, but with a teachers’ room and a night keeper’s room.

Director Yasuike is walking around and ringing the bell in the highland’s morning mist. He is telling each household to join the unofficial party to celebrate the completion of construction. Home cooking was brought in, and the celebration began at the branch school that smelt fresh wood. As sake started to take effect, each struggle to date were clearly remembered and tears of joy or vexation overflowed. To express the feelings beyond description, without a cause, a fight started and someone got a bleeding nose. “Stop it! Are you defiling the new schoolhouse with blood?” It was a shriek of Director Yasuike. “What was it that supported us until now? It was only mutual trust. You were serious because you had no money. You united because you were poor. Riches is not always a treasure. The joy of today is not shared with the five who dropped out”

Director Yasuike, who stood to make a speech, was so moved that he cannot say a word on the podium. Adults and children alike looked down and sobbed. After the ceremony, the children performed a play. They had done their best to practice for a month for this day.

We laughed and applauded from the bottom of our hearts for the first time in a long time. In June, 1941, Director Yasuike was ordered to be the chief of the agricultural land section of Nara prefecture. Come to think of it, for these three year, Director had endured in dilemma between his status as a government official and personal feelings towards us. Have his superiors who used to frown at him changed their attitudes toward Director when he completed the Yatsugatake reclamation project, and under the alarming war situation, increasing the food productivities became an important national policy? We are repaying the debts of the branch school construction. The farmers union has just launched the landed farmer establishment project. But now, we are on our own. We cannot restrain a young man with a future forever.

We cried at Kiyosato Station. Farewell, teacher Yasuike, our beloved Director who was our father and brother.

Good bye, good bye.

Half a year had passed after Director had left when the Pacific War broke out. Many men from this settlement departed to the front and some never came back. We heard that the Ogochi dam sytem construction came to a halt.

Meanwhile in October 1944, all debts were repaid and landed farmer establishment project was completed. We wrote to Director Yasuike for the first time in a while. “Thanks to you, we have lawfully become landlords. It is like a dream…” Quite a while after Director left, we came to learn of a fact for the first time.

For more than a year after we came, fertilizers, seeds and seedlings were distributed. However we believed that they were all from the prefecture, those were, in fact, paid by Director. Director had spent most of his yearly salary for us. The prefecture which did not allow us to have the least amount of money for agricultural operation, in conclusion, just gave each of us a hoe. After the war, to break through the food shortage, Japan emphasized reclamation policy and new settlers were sent also in to Kiyosato one after another. The first group of those are the ones that now reside in Asahigaoka district. They were astonished to see how we, their predecessors by eight years, lived so poorly. Even though it was Japan that emphasized the policy, in the end, each and every fund burdens the settlers as debts. Following Asahigaoka, settlers kept increasing in Higashinemba and Shimonemba, who also had strings of difficulties. It was around that time when Dr. Paul Rusch of Rikkyo University opened Kiyosato Agricultural Community Center by remodeling a university facility that existed since before the war. Buildings such as a grandiose church, an experimental farm, a hospital and a library were erected and communication with the local farmers often took place. For us, farmers, the county fair held every August was especially the largest festival. We competed against each other in contests of cows and pastures. Study groups for agricultural techniques and dairy farming were there, too. Moreover, there was time during which they provided milk for elementary school pupils. In return, we used to mow the grass around the farm.

Eventually, young people from the city started to visit Kiyosato. SEISEN-RYOU, the accommodation building at the Community Center became very popular. Kiyosato gradually became touristy. Our group of people started to switch their business to inn management around 1969. I also manage a dairy farm and an inn myself, now. The village of Kiyosato has merged with four other nearby villages to become the town of Takane. In 1971, in the corner of a meadow in the highland, our cemetery was established. The orderly rows of twenty-three gravestones are facing our hometown, Tabayama village. As if to watch over us, the very last one stands for our teacher Yasuike. It was build before his passing away.

In the back of the gravestone, our teacher had it engraved “Emotional heart clears the way to paradise—Okio” Not many of us who shared joys and sorrows are left, now. Someday, all of us will rest in peace under these granite stones looking up at the blue sky in the highland.

The construction of Ogochi dam system resumed in 1948 and the dam was established in 1957. Then, it was renamed Lake Okutama to be loved by people as a recreational place of Tokyo. Surrounded by the greens, is the lake water as blue as the sky in Kiyosato?

*This text was reprinted from “Emotional Heart Clears the Way to Paradise”